Close

The Bell Tower

The Bell Tower

The works presented in The Bell Tower, draw on the notion, or the experience, of something profoundly simple: sound. It is a subject, which, I’ll be the first to admit, does not readily lend itself to such a famously silent, stealthy and still medium; which, of course, is photography. But it is a subject, which I felt, couldn’t be escaped; it seemed to claw away at me, at my thoughts and feelings, as if it were something which sought to devour and assimilate me—it demanded I enter it, into its cave, constructed of a dark, eternal echo; an embrace, so strong and absolute, that I feared, if I did not accept it, I would lose the breath which gave rise to my voice.

The source of this sound, is, of course, that moulded piece of metal, found at the top of the bell tower; the bell I found there, hung, dusty and grey, when I first laid my eyes upon it. It was coarse, like a raw and overused throat; I imagined it groaning then, bellowing, as though it were a voice box, of a metal giant. I climbed down from the ladder, which I was perched on, and continued to move around the rest of the building. The rooms, were not quite derelict, but not quite of this time, either. They lay rugged and bare. And in parts, torn and distressed. I thought them to be one of two things: firstly, desperately awaiting the arrival of something; secondly, trembling, in the aftermath of something’s visit. I guess, you could say, they looked like children —not the kind you’d imagine, though, happily playing in the park, but the kind from a novel, from a place where love is often lost, and hard to come by; perhaps, a Victorian story, I told myself. They were all sorts of kind of’s: kind of lost; kind of sad; kind of not really there; just floating, latent; kind of dead behind the eyes. It was poignant, and I couldn’t help but think of a doctor, who is attracted to broken things, which he cannot ever fix. I left with that sense, welling up inside of me.

I went home that afternoon and began to contemplate that building which laid bare, bereft of the thingness which once made itself, itself. The bell has not rung for many years, I was told, when I first attempted to seek it out. That knowledge niggled away at me. Like an incessant itch, that I just couldn’t scratch. There was something about it that I couldn’t quite put my finger on. Some time passed, and, after a while—after I’d done my washing, had my dinner, and made my bed—it struck me: I considered the bell, not as an instrument, but as an object. Needless to say, all instruments are objects, but when something is associated to Art, or is an object which makes Art, produces Art, of which I’d say, the bell, which makes sound (which turns into music), is, then, in a sense, its designation as an object becomes slightly trickier; well, it does for me anyway. Maybe it’s because Art doesn’t generally have a function—a function in the quotidian sense—and here, it dawned on me: instruments are the only things which are both Art and function. You may also be sat there thinking: when does a sound, become music? When does a noise, become Art? These are very valid questions, and they produce, like most things, gaping holes in my logic. And I think, perhaps, I’ll leave them for you to answer.

Now, my curiosity has got the better of me, and I’ve lead us down a path— although, closely related—which would eventually lead us to the wrong wood. What is important is the idea of the bell as an object. Keep hold of that. And what, may I ask you, is the most common attribute among objects? They have a function. This glass, which sits next to me, as I write, has a function: to hold liquid. This pen, too, naturally, does its thing: it writes. So what does it mean for a thing to no longer do what it was born to do? A ship out of water. A bird with clipped wings. A bell that does not ring. It speaks to me of something which we don’t really like to deal with often: the fundamental nature of things; namely, the enduring absence and presence of everything. If something loses its function, does it also lose its presence? Does it become absent in a world concerned with an enduring presence? And I truly sat there, bolt up right, in my bed that night, with those very same thoughts swirling around my head; sleep evaded me, a fugitive from my grasp, as my thoughts, flipped and turned; but, I could not escape the deepest of my thoughts that night: a question, as to whether, or not, the bell, may make music once again. It was like a children’s story, reaching the end of a tape; or sand, running out, in an hourglass.

In any case, before it is lost to the sea of time, might we, briefly, consider what the bell brought us. It is believed to come from the Old English, bellan, meaning to roar, and from this, grew a word which we have already used, bellow (a loud booming voice); something, which, you’d almost certainly hear, amongst the hustle and bustle of the city. And actually, that reminds me: let’s say you’re hurriedly walking down the street, dodging elderly pedestrians, and weaving in and out of slow moving, lost, tourists, and it’s then, it’s then you hear it, the sound of a bell ringing. It becomes a sound of recognition: it tells the time; it tells of marriage; it tells of mass; it tells of death; it tells of victory; it tells of life events. But it does so in an instant— doesn’t it? How remarkably simple, I thought. It was a marker in our lives when we only had the sun and bells to mark things. The sound moves through us, and, in doing so, we recognise, distinguish and categorise it; in this respect, the bell, and its sound, becomes analogous, to the human voice: to the human experience of speaking and listening; it saddens us, lifts us, and essentially, moves us. They are, what the artist, Jannis Kounellis, spoke of: the bells represent language, a magnified human voice—and the enthusiastic roar of liberation. They are not only found amongst our cities, but lie, hidden away, like acorns, in the earth, in the ground of our art and our stories; such as Macbeth by William Shakespeare, Peter Pan by JM Barrie, The Bell by Iris Murdoch and Notre Dame de Paris by Victor Hugo. They ignite adventure, and have followed us across oceans.

This might all be a rather roundabout way of saying something which I’d decided, a couple days after my initial visit. I’d landed on a direction, one I was intent on following; the course was calculated, and the path was set. I was interested, you see, in listening; in hearing the sound the bell makes, for all those reasons I just mentioned. However, as it happens, that wasn’t entirely possible. So, I set about working with a medium that continues to surprise and support me, as though, when I uncover another facet of its character, I discover something new about myself. To ring a bell, is to awaken a memory, and to make a photograph, is to live it.

The Sound Floods,

My Body,

My Vessel

Text written by Alexander Mourant, 2020.

The Old Rectory, 2021

The Bell Tower

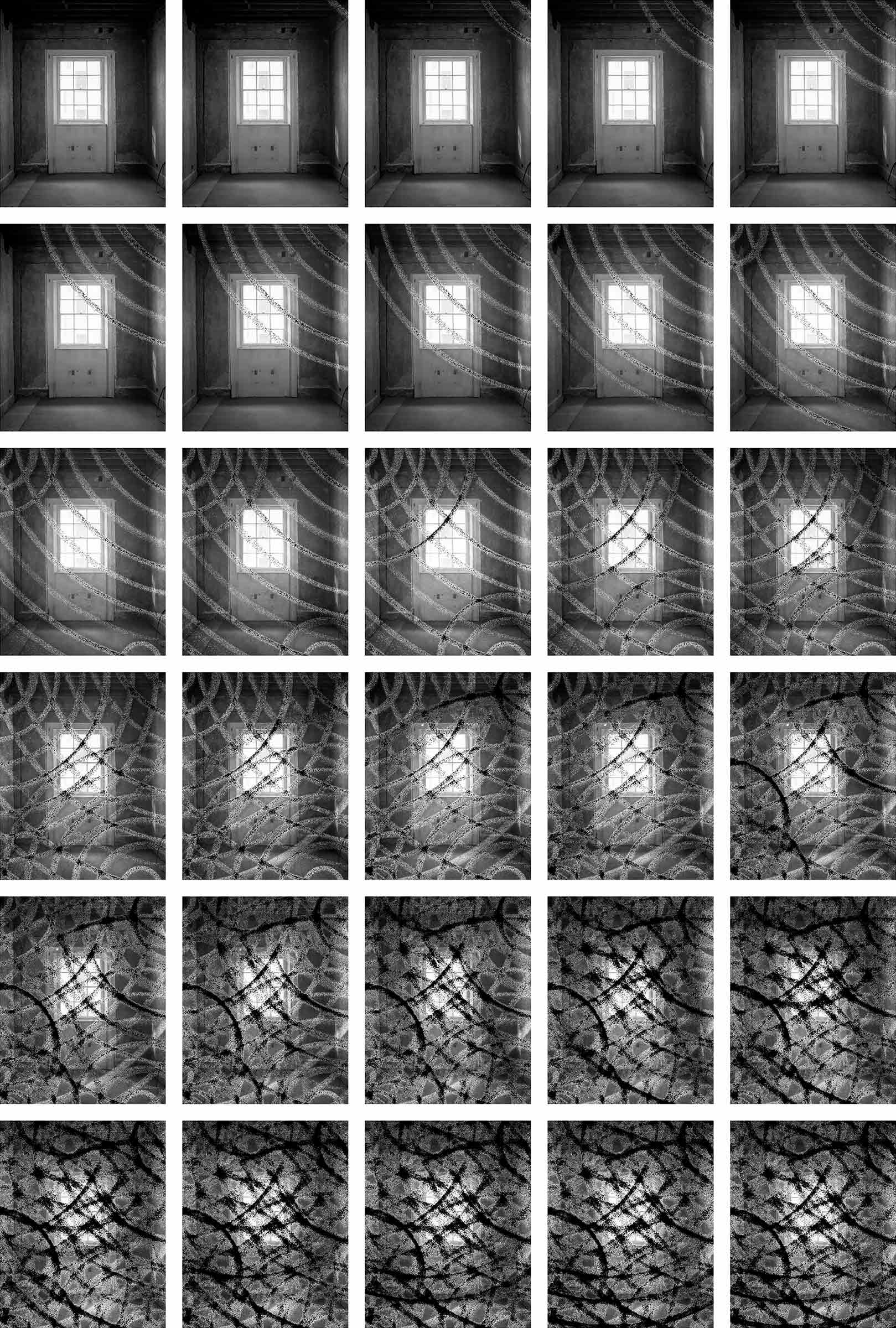

An Attempt to Flood the Photograph, 2020

The Old Rectory, 2021

The Bell Tower

Mechanism, 2020

The Old Rectory, 2021

The Bell Tower

AATFTP & Mechanism, 2020

Movement VI, 2020

Movement XIII, 2020

An Attempt to Flood the Photograph, 2020

168cm x 116cm, ed. 3 + 1AP

Digital silver gelatin print

Dust Dances Around Itself, 2020

86cm x 106cm

Digital silver gelatin print

Bespoke white box frame

Edition of 3 + 1AP

Vessel I, 2020

106cm x 86cm

Digital silver gelatin print

Bespoke white box frame

Edition of 3 + 1AP

Vessel II, 2020

106cm x 86cm

Digital silver gelatin print

Bespoke white box frame

Edition of 3 + 1AP

Vessel III, 2020

106cm x 86cm

Digital silver gelatin print

Bespoke white box frame

Edition of 3 + 1AP