Close

I Could Not Tell Glass From Air

I Could Not Tell Glass From Air

To speak of this work, is to attempt to do something quite strange. You see, to speak, or to articulate, is very often than not, a means of defining something: to make it known, recognised, to form boundaries of what it is and how it works; seemingly satisfying for both I, the artist, and you, the reader. And it is only now that I recognise, after quite a few years of thinking the opposite, of how troublesome that can be, how dissatisfying, for the work to be betrothed to words before it is even felt on its own; and feeling, or rather, sometimes, the lack of it, is what drives us forward.

Let me put it in another way: what I’ve never really understood, as a young artist, when mingling, say at a gallery opening, or at a talk, is when someone would utter the illustrious phrase: it’s a research project; firstly, it’s normally said in a tone designed to condescend, as if I just wouldn’t get it; secondly, and what I feel might be the true reason: they don’t really understand it yet, they are embarrassed, and sense if they were to divulge it, they would jeopardise the work itself. I’ve never really got that: a trepidation in seeing it slip through my hands, like sand between my fingers. I’ve always been quite comfortable speaking about it, to most people, whether it was rehearsed or not, I knew the rhythm. But here, here in the present, emerges the slippage between then and now, as today, at this very moment, I do not know it. I feel adrift in a sea of otherness; it pervades me, washes over me, like goosebumps on my skin. The work seeks to defy words. And as easily as glass cracks, I do not wish to break the image you have formed of it. In the light of this, I wondered whether you’d be interested in navigating us a little differently: instead of reciting what I think, and lying in the process, might we choose to discuss what surrounds it? I feel them shimmering like stars, as these clusters of thoughts, spin, orbiting around us. Through them I have learnt to see further and deeper than ever before.

The title draws from the notion, or the experience, of double taking: a glance, which often reveals something unsuspected, or overlooked. What I thought I saw is not what I thought I saw. It reminded me of my initial visit to the site of the work, the greenhouse, and to the trickery its glass panels played, on my mind and my eyes. To visit it, was to enter a world of appearances, a curiously fractured and refracted world of sight; a field of disbelief, and illusion. This sensation was supported by decades of decay, as the greenhouse, fallen into disrepair, only faintly resembled itself, like a face, or a body, withering, sixty years on from the date of a photograph. Through this ruin form I found within it a kind of disruption, or an assault, upon the usual order of things. I was drawn to it, hungering for its flux in time; I saw it as a vessel, a ship of glass, floating amongst a sea, as black as the night, crashing against great waves of foliage. It is something which still pushes me toward a profound question: what is the truth of it? The truth of what shrouds us, and, momentously, the nature of seeing itself. I felt akin to André Breton, who desired to live, entirely, in a glasshouse, for all the clarity and cohesion it would bring to the character which was himself. I sensed I would find things there, or an inquiry as to why it is, and how I perhaps, came to be there.

It dawned on me a while ago that the greenhouse is essentially a house of windows. A structure, or a sculpture, for seeing, and seeing through. Baudelaire speaks about windows, and how the world can only, truly, be seen through windows, and this seeing needs glass, it needs the separation and distance provided by it, in order to see the outside for what it is. And somehow it’s the distance, mediated by the glass, by not touching it, that makes the sensation of seeing, seem further; moreover, glass is a material which exists in the in-between, it is liminal (a term born in The Forest of Symbols by Victor Turner): dividing interior and exterior; inside and outside; here and there. It exists in a grey space, but it is a threshold too. And does this description not remind you of another? For me, I felt it analogous to the camera; more so, the children of it: photographs. Physically, they are the in-between: there’s me, here, and over there, there’s the thing, the subject; and what do I place in-between those two things: the camera, of course. What’s more, not to be Barthes about it, but, it’s not quite dead, and not quite living, is it? The photograph, I mean. It exists in a space of neither day nor night. Of neither life nor death. It’s a twilight art, as Sontag said: it’s a marker for a reality within itself. And I found that intoxicating. To be walking inside it, amid photographs and a structure, which I came to see as the apparatus of seeing, rupturing, in front of my eyes.

Frustratingly, I’ve found just one reading will never do; it’s constantly reread, like my favourite, battered, old novel, thrown to the floor; the ink on the page, so damaged by light and touch, begins to fade—the text is no longer black. That path became grey and winding, and it suited me: whenever I say, think or do anything, I can always see the reverse, and justify the opposite. Perhaps, I thought, I had absorbed the entropy of it, the energy of the site itself, to live as the structure, whose images faded inside of me. Robert Smithson frequently discussed the idea of energy transfer, but there was one comment in particular, upon producing Glue Pour (1969), which struck a chord with me. He spoke of the decisive event which solidified Duchamp’s The Large Glass (1915–1923): the cracking of it. During the movement of the work from A to B, the work though carefully packaged, famously, shattered in transit. Smithson saw Duchamp’s attempt to safely transport the work as being an endeavour to overcome entropy; however, against your greatest efforts, it’s the destiny of glass, to eventually break. He aligned it with the entropy found in geology, where everything is gradually worn down. And Smithson felt that in association to the art object, and Duchamp too, embraced it, realising his glass only became the Large Glass, on experiencing its change into something similar, but again, decidedly other. And what they touched upon, I feel is what art is: the energy of something, changing into something else.

Through my work, I began to realise the materials which made up this ruin, had departed the realm of the functional, operational, and in doing so, had entered a world of the pure and absolute. Here we could deal with the fundamental nature of things: the enduring absence and presence of it, and of us. As it oscillated between the two, between life and death, we weren’t witnessing the loss of images, and the loss of meaning, rather, the breeding of things, and the presence of the energy that is art. The growing, adding, multiplication of things which gave us air to fill our lungs, and opposed the habitual reading of photographs: a distillation or a crystallisation of things, into minerals, light and time. So the site became a paradox for me. At first, I sought to enter a world of obliterated images, the end of the image, you could say, and time itself, a void, an abyss, much like Klein’s The Void (1958), but what precipitated, through traversing the abyss, through the image of it, was an action not too dissimilar to Alice falling into Wonderland: I learnt a way of feeling which was beyond my apprehension. I guess, it was the surreality of it, of learning that which surrounds you, was a clear, glass box, the atmosphere of which compresses you, until at last, you were urged by your last breath, to reach out, and touch the surface. When you went to touch the glass you realised it was not glass at all, but air.

I suspect, without knowing it, I’ve found myself in the midst of it, in an ever expanding, ever turning, spectrum of research. I’ve learnt many others have found a solitude in it, lying, comforted, underneath sheets of glass: Derek Jarman, use to literally sleep inside a greenhouse in his cold, lofty flat, an emblem of his undying love for the botanical, and the distance he felt between his identity and social acceptance; Agnès Varda’s piece, The Greenhouse of Happiness (2018), was constructed entirely out of original 35mm negatives, and mused on the nature of nostalgia, as her work underwent a metamorphosis, becoming a literal house of cinema; Maurice Maeterlinck, the Belgian playwright, released a book of poems, titled Hothouses (1889), which delved into the nature of the soul, and the subconscious under glass; and lastly, Léon Spilliaert, the symbolist painter, who was greatly influenced by the aforementioned writer, became infatuated by their contained atmosphere, filling his depictions with a strong brooding colour and subtle luminescence. As many others have before me, I shall continue to learn from it.

Falling through;

falling through;

falling onto glass.

Text written by Alexander Mourant, 2020.

Shelter, 2020

38 mixed size (piece scale: 4m x 9.2m)

Silver gelatin hand print (photogram)

Aluminium mount + steel tray frame

Unique

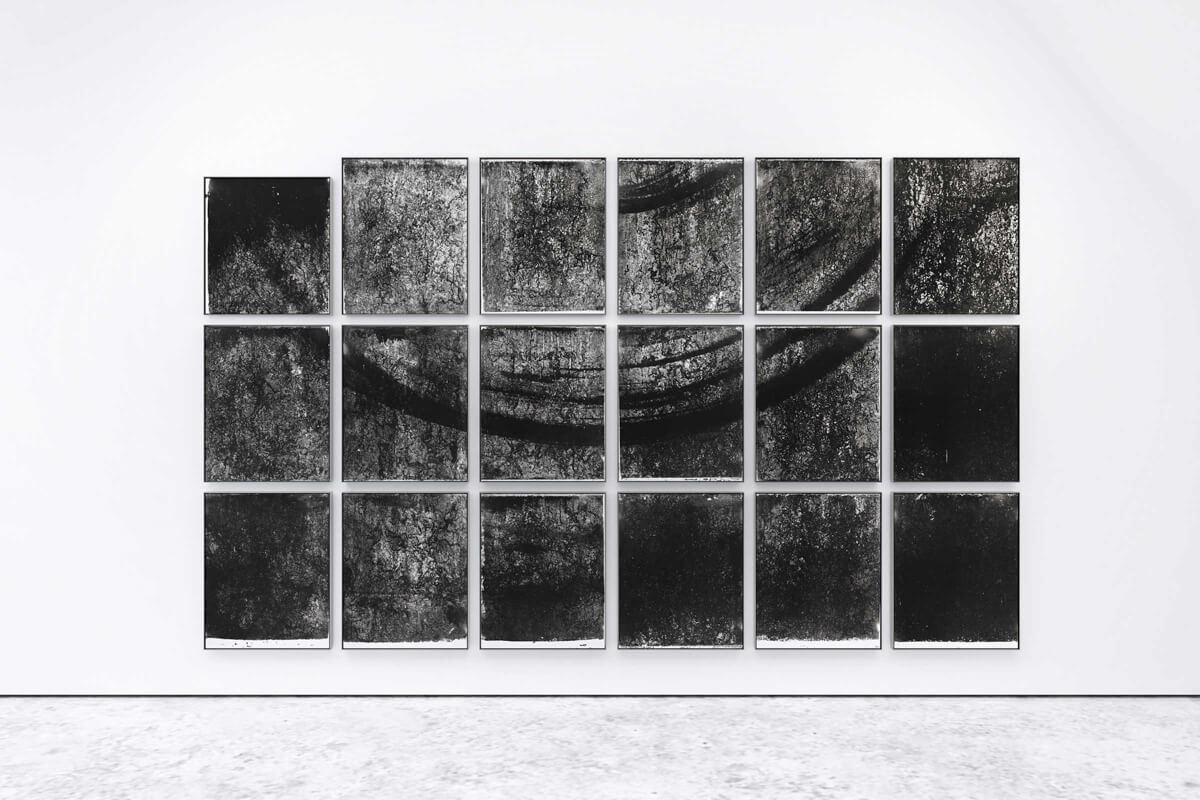

Shelter, 2020

38 mixed size (piece scale: 4m x 9.2m)

Silver gelatin hand print (photogram)

Aluminium mount + steel tray frame

Unique

Shelter, 2020

38 mixed size (piece scale: 4m x 9.2m)

Silver gelatin hand print (photogram)

Aluminium mount + steel tray frame

Unique

An Image That Holds Its Heat (IV), 2024

48 x 45 x 45cm

Direct to media print on glass, cast iron

Unique

An Image That Holds Its Heat (IV), 2024

48 x 45 x 45cm

Glass, cast iron, soil

Unique

An Image That Holds Its Heat I, II & III, 2023

45 x 74 x 61cm each

Direct to media print on glass, steel

Unique

An Image That Holds Its Heat I, II & III, 2023

45 x 74 x 61cm each

Direct to media print on glass, steel

Unique

An Image That Holds Its Heat I, II & III, 2023

45 x 74 x 61cm each

Direct to media print on glass, steel

Unique

An Image That Holds Its Heat I, II & III, 2023

45 x 74 x 61cm each

Direct to media print on glass, steel

Unique

An Image That Holds Its Heat I, II & III, 2023

45 x 74 x 61cm each

Direct to media print on glass, steel

Unique

An Image That Holds Its Heat I, II & III, 2023

45 x 74 x 61cm each

Direct to media print on glass, steel

Unique

Part of a Whole, 2020/2022

Diptych, 24 x 20” each

Silver gelatin hand print

Moss, glass, walnut

Unique

Vitrum IX, 2019

Print: 25.4cm x 20.32cm

Digital silver gelatin print

Mount + black aluminium frame

Edition of 5 + 2AP

Vitrum IX, 2019

Print: 25.4cm x 20.32cm

Digital silver gelatin print

Mount + black aluminium frame

Edition of 5 + 2AP

A Gesture of Brambles, 2019

17: 61cm x 51cm + 1: 56cm x 51cm

Silver gelatin hand print

Aluminium mount + steel tray frame

Unique

A Gesture of Brambles, 2019

17: 61cm x 51cm + 1: 56cm x 51cm

Silver gelatin hand print

Aluminium mount + steel tray frame

Unique

,-2019.jpg)

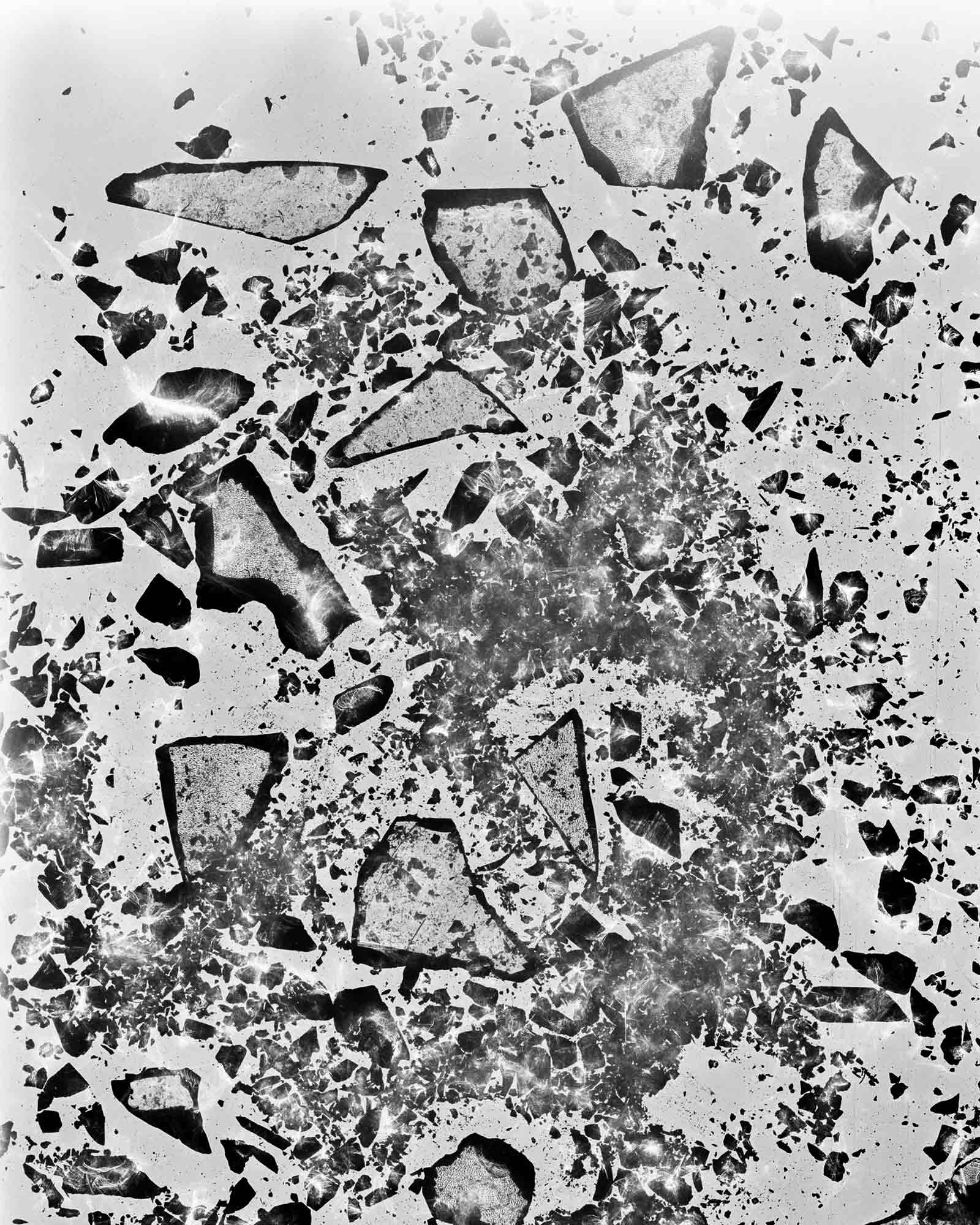

Fall I & II, 2019

Prints: 156cm x 126cm

Digital silver gelatin print

Edition of 5 + 2AP

Vitrum III & Vitrum IV, 2019 & 2018

Print: 10cm x 8cm

Frame: 44.5cm x 38cm

Silver gelatin print Mount + aluminium frame

Edition of 5 + 2AP

Vitrum III, 2019

Print: 10cm x 8cm

Frame: 44.5cm x 38cm

Silver gelatin print + aluminium frame

Edition of 5 + 2AP

Vitrum IV, 2018

Print: 10cm x 8cm

Frame: 44.5cm x 38cm

Silver gelatin print + aluminium frame

Edition of 5 + 2AP

Vitrum V, 2018

41cm x 51cm

Silver gelatin print

Walnut frame

Edition of 5 + 2AP

Vitrum I, 2019

102cm x 81cm

Digital silver gelatin print

Walnut frame

Edition of 5 + 2AP

Vitrum II, 2019

156cm x 126cm

Digital silver gelatin print

Walnut frame

Edition of 5 + 2AP

Vitrum VI, 2018

156cm x 126cm

Digital silver gelatin print

Walnut frame

Edition of 5 + 2AP

Vitrum VII, 2018

126cm x 156cm

Digital silver gelatin print

Walnut frame

Edition of 5 + 2AP

Vitrum VIII, 2019

102cm x 81cm

Digital silver gelatin print

Walnut frame

Edition of 5 + 2AP

Vitrum X, 2019

102cm x 81cm

Digital silver gelatin print

Walnut frame

Edition of 5 + 2AP

Vitrum XI, 2018

156cm x 126cm

Digital silver gelatin print

Walnut frame

Edition of 5 + 2AP